Listen While You Read 🎧

Hit play and let the story set the mood as you dive into this remarkable moment in cigar history.

JFK cigars are more than just a quirky footnote in history — they’re tied to one of the most famous embargoes of the 20th century and a story that blends ritual, irony, and Cold War politics. Imagine being the leader of the free world, standing at the center of the Cold War, about to sign a document that would change history.

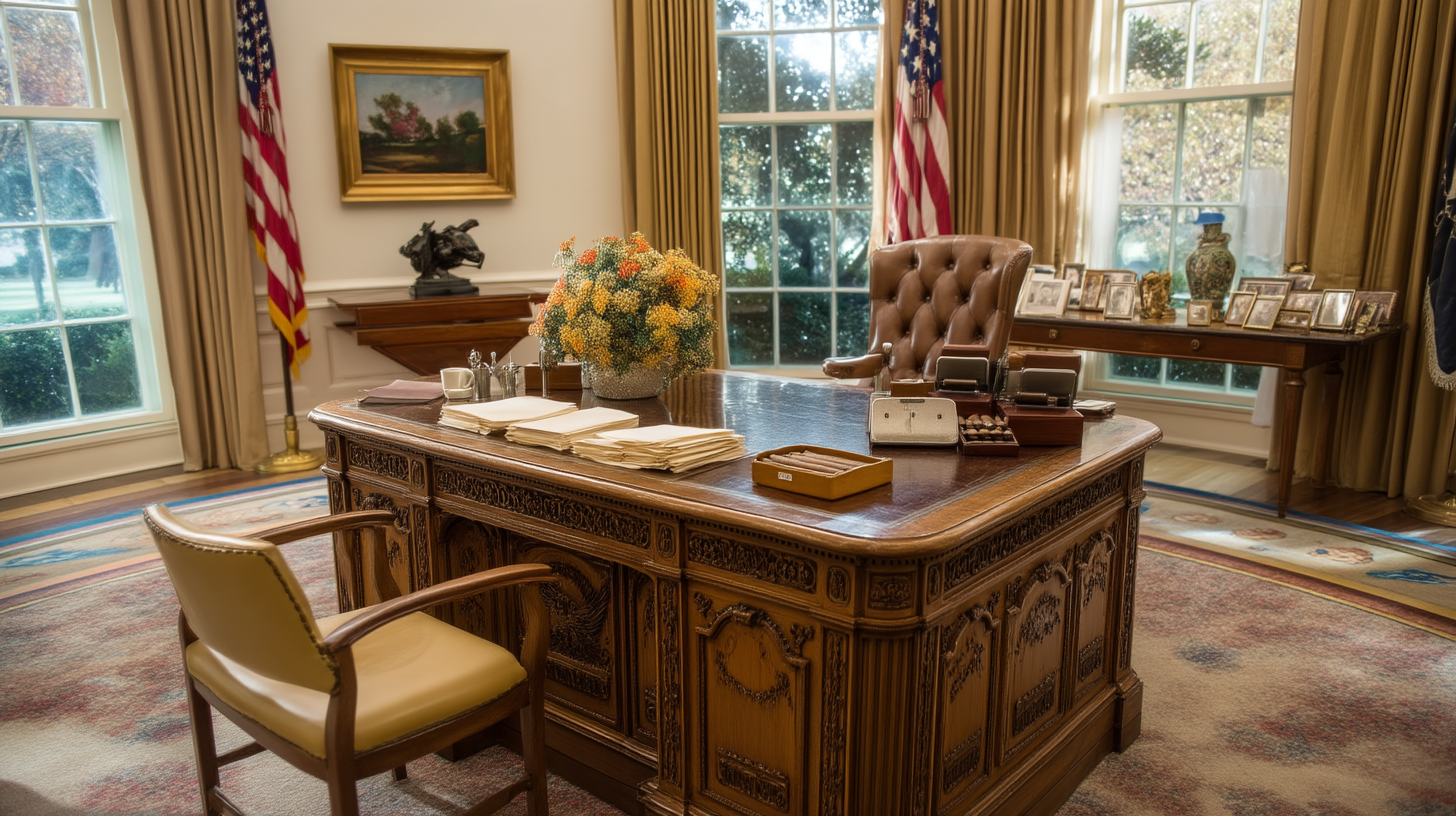

Imagine being the leader of the free world, standing at the center of the Cold War, about to sign a document that would change history. Tensions with Cuba are boiling, advisers are pacing, and the Oval Office hums with the weight of global consequence. And in the middle of it all, John F. Kennedy makes a request that seems almost laughably ordinary: “Pierre, can you get me about a thousand cigars?”

That single sentence would spark one of the most enduring legends in the world of cigars. It’s a story about irony, indulgence, and the strange ways that personal rituals intersect with political history. Did JFK really hoard over a thousand of his beloved H. Upmann Petit Coronas the night before the embargo? Or is this tale more myth than fact, polished smooth by decades of retelling?

Either way, the legend endures — and for cigar lovers, it’s one of the most fascinating footnotes of the 20th century.

Key Takeaways 📝

-

🚬 John F. Kennedy’s favourite cigar was the H. Upmann Petit Corona, a small but flavorful Cuban smoke.

-

📦 On the eve of the 1962 Cuban embargo, JFK allegedly stockpiled more than 1,200 cigars through his press secretary, Pierre Salinger.

-

🌍 The embargo reshaped the global cigar industry, pushing production into the Dominican Republic, Honduras, and Nicaragua.

-

🕵️ Legends of CIA exploding cigars and White House rituals add intrigue and humour to this Cold War tale.

-

🔥 The story blends fact and myth, showing how even influential leaders cling to small personal comforts in moments of history.

JFK’s Favourite Smoke — The H. Upmann Petit Corona

When people picture presidents with cigars, the first image that comes to mind is usually Winston Churchill, puffing away on something so large it could double as a table leg. John F. Kennedy? Not so much. He was subtler, more refined in his habits. Instead of the oversized Churchill vitola, JFK preferred a smaller and more balanced option: the H. Upmann Petit Corona.

The Petit Corona was, and still is, a Cuban classic. At about five inches long, it’s not a marathon smoke — more like a quick interlude in a busy day. For Kennedy, it was the perfect fit: flavorful enough to savour, yet compact enough to enjoy between meetings in the Oval Office. Unlike the blustery prop Churchill waved around, JFK’s cigars were never about showmanship. They were private indulgences, tucked into stolen moments.

Friends recalled how Kennedy would sometimes leave half-smoked cigars behind when called into urgent meetings, the ashtray evidence of a ritual interrupted by history. And when the schedule finally slowed, his cigar became a signal — an unspoken cue that business was over and conversation could begin. At one White House gathering, guests waited politely until Kennedy reached for his own cigar, lit it, and leaned back. Only then did everyone else follow suit.

For a man navigating nuclear standoffs and Cold War politics, a Petit Corona wasn’t just tobacco wrapped in a delicate Cuban wrapper. It was a pause button; a reminder to breathe. And, as we’ll see, it was the very cigar he would go to extraordinary lengths to secure before reshaping the cigar world forever.

The Cuban Embargo of 1962

By the early 1960s, the relationship between the United States and Cuba had gone from tense to toxic. Fidel Castro had seized American-owned businesses, aligned himself with the Soviet Union, and turned Havana into a thorn in Washington’s side. For Kennedy, who had already endured the Bay of Pigs fiasco and was staring down the Cold War, action seemed inevitable.

The embargo wasn’t a single stroke of the pen—it was the culmination of escalating sanctions. Sugar imports were already cut. Aid had dried up. But in February 1962, Kennedy issued Proclamation 3447, the formal order that shut down nearly all trade between the U.S. and Cuba.

***According to the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library, the embargo was formalized in Proclamation 3447 and took effect in February 1962.

And here’s the kicker: cigars were not exempt. Some had lobbied for a carve-out, citing the prestige of Cuban tobacco and its significance to cigar culture. But manufacturers in Tampa and beyond pushed back hard, arguing that allowing Cuban cigars would devastate their own industry. Kennedy sided with them. The embargo became total.

From that moment forward, Americans could no longer legally purchase Cuban cigars. What had once been an everyday indulgence suddenly became forbidden fruit. Overnight, the H. Upmann Petit Corona went from presidential ritual to contraband legend.

For the wider world, the embargo symbolized Cold War hostilities. For cigar lovers, it meant something more personal: the sudden loss of the most famous smokes in history. And for Kennedy, it meant his late-night request to Pierre Salinger was more than indulgence—it was insurance.

The Famous 1,200 Cigars Story

Here’s where history takes a turn that feels more like a movie script than a government memo. One evening in early 1962, just before the Cuban embargo was to take effect, President Kennedy called in his press secretary, Pierre Salinger. The request wasn’t for a speech draft, a briefing, or an intelligence report.

It was for cigars.

“Pierre,” Kennedy said, “I need you to get me a lot of cigars—very quickly.” When pressed on how many, the President replied: “About a thousand Petit Upmanns.”

Now imagine being Salinger at that moment. The world is on the edge of nuclear confrontation, and your boss—the leader of the free world—has just given you what amounts to the most important cigar errand in American history.

Salinger sprang into action, combing through tobacconists all across Washington, D.C.. He called in favours, worked his contacts, and by the next morning, he had done even better than expected: more than 1,200 H. Upmann Petit Coronas stacked and ready.

When he proudly reported back, Kennedy grinned, reached into his desk, and pulled out the paperwork. The story goes that he signed Proclamation 3447—the official order banning Cuban goods—only after his own humidor was secured.

Now, let’s be honest: historians have pointed out a wrinkle here. The embargo paperwork was dated February 3, 1962, and officially went into effect on February 7. So the timing of the “overnight mission” may have been more flexible than the legend suggests. But like all great stories, the truth and the myth are now forever intertwined.

And really, isn’t that the perfect irony? Kennedy protected his 1,200 cigars first, and then cut off the rest of the country.

**Cigar Aficionado recounts how Pierre Salinger raced through Washington, gathering more than 1,200 Petit Coronas before Kennedy signed the embargo.

How the Embargo Changed the Cigar Industry

When Kennedy’s pen touched paper in 1962, it didn’t just close the door on Cuban trade—it reshaped the entire cigar industry. For Americans, the beloved Cuban was suddenly gone, like a favourite bar that shut its doors overnight. What followed was both a crisis and an opportunity.

Cigar makers who had fled Cuba began to rebuild elsewhere. Romeo y Julieta, Montecristo, Partagás, and others set up factories in the Dominican Republic, Honduras, and Nicaragua. They carried their recipes, their rolling traditions, and even their brand names across borders. The same cigar bands that once wrapped Cuban leaf were now placed on blends from entirely new soil.

It was a strange duality: one brand, two realities. On the island, Cuban Habanos continued to be rolled with their trademark richness. Abroad, exiled families recreated their heritage using non-Cuban tobaccos. Both versions were authentic in their own way, but only one could be sold legally in the United States.

The embargo also fueled decades of trademark battles. With Cuban companies unable to defend their brands in U.S. courts, American importers claimed rights to the same names. Even today, you’ll find “Cuban” brands with two very different lineages depending on where you buy them.

And here’s the irony: by trying to punish Castro, the embargo ended up boosting entirely new industries. The Dominican Republic blossomed into the world’s largest exporter of cigars. Nicaraguan and Honduran brands rose to prominence. American smokers, cut off from Havana, found themselves falling in love with new blends and new traditions.

What started as a Cold War punishment became a global shakeup. And all because Kennedy wanted his cigars, and then made sure no one else could have them.

Myth, Fact, and Cold War Anecdotes

If the embargo gave us irony, the Cold War gave us absurdity. Cigars weren’t just luxury items in the 1960s; they became props in some of the strangest stories of the era.

Take the CIA’s exploding cigar plot. Yes, it really appeared in brainstorming sessions. The idea was simple: slip Fidel Castro a cigar that would blow up in his face. Other schemes included poisoned cigars and chemically treated smokes designed to make his famous beard fall out. None of them came to fruition, but they underline how deeply cigars were woven into the Cold War imagination — part indulgence, part weapon.

Kennedy himself had his own cigar rituals that bordered on legend. At one White House dinner, guests held back, cigars unlit, until JFK quietly reached into his pocket and struck a match. That small flame became a signal: business was over, and they could relax. For a man under constant pressure, a cigar wasn’t just tobacco — it was punctuation.

Then there were the half-smoked cigars he would leave behind in ashtrays around the Oval Office. Advisors joked they were as much a marker of Kennedy’s schedule as his official calendar: little stubs of calm, interrupted by the next crisis.

Some of these stories are verifiable, while others reside in the hazy overlap of history and myth. But they all remind us of the same truth: cigars, in Kennedy’s time, carried a weight beyond leisure. They were symbols of status, of leadership, and sometimes of folly. And whether through whispered anecdotes or CIA files, the humble cigar managed to leave its mark on the high drama of the Cold War.

Conclusion — A Legacy Sealed in Smoke

In the end, the tale of JFK and his 1,200 cigars is more than a quirky anecdote. It captures the duality of power and humanity: a president navigating nuclear showdowns, yet still carving out time for his favourite Petit Coronas. It shows us how personal rituals can intersect with history in ways that ripple for decades.

The Cuban embargo of 1962 is still with us today, and the mystique of the forbidden Cuban cigar remains stronger than ever. Meanwhile, the industry Kennedy helped transform continues to thrive in the Dominican Republic, Nicaragua, and Honduras.

So was Kennedy’s cigar run clever foresight, pure indulgence, or just a legend polished by retelling? The truth probably lies somewhere in between. What we do know is this: on the night America’s cigar story changed forever, the President of the United States made sure he had his humidor filled.

And that, more than any treaty or proclamation, is the detail cigar lovers will never forget.

For more Cigar & Whiskey stories, subscribe to Smoke Signals on Substack.

Frequently Asked Questions

Curious about JFK’s cigar habits and the embargo? Here are some quick answers to the most common questions:

What cigar did JFK smoke?

John F. Kennedy’s favourite was the H. Upmann Petit Corona, a small Cuban cigar known for its balanced flavor and approachable size. Unlike Churchill’s massive smokes, JFK preferred something subtle, elegant, and practical — perfect for a quick ritual between meetings in the White House.

How many cigars did JFK stockpile before the embargo?

According to press secretary Pierre Salinger, JFK ordered “about a thousand” cigars the night before signing the embargo. Salinger returned with more than 1,200 Petit Coronas. While some details are debated, the story has become one of the most famous anecdotes in the history of cigars.

Did JFK really sign the embargo right after receiving the cigars?

The legend says Kennedy signed Proclamation 3447 immediately after securing his cigars. In reality, the paperwork was dated February 3, 1962, and took effect February 7. Still, the timing of the story — cigars first, embargo second — has cemented its place in Cold War lore.

How did the Cuban embargo affect the cigar industry?

The embargo forced cigar lovers to look beyond Cuba. Exiled brands like Romeo y Julieta and Montecristo reestablished in the Dominican Republic, Honduras, and Nicaragua, sparking trademark disputes but also building thriving new industries. Today, those regions rival Cuba as the heart of premium cigar culture.

Bo Kauffmann is the voice behind Cigar and Whiskey Guide and Smoke Signals on Substack, where he shares expert reviews, pairings, and lifestyle insights for enthusiasts around the world. A longtime cigar lover and bourbon explorer, Bo blends storytelling with deep knowledge to help readers savor every pour and every puff.